In my last post, I talked about how America had depressed oil prices by increasing its supply. Recall this graph which shows that the supply glut is primarily caused by increased American supply (the top pink line is America):

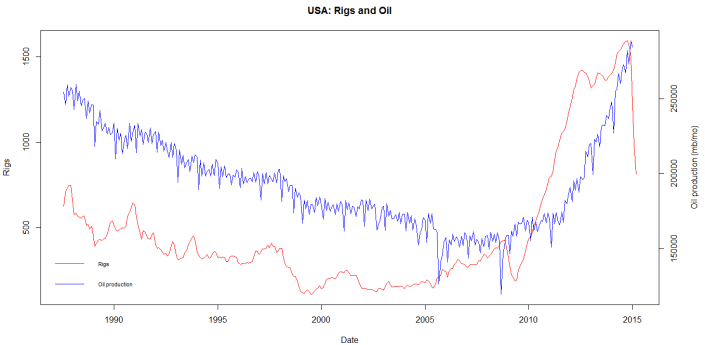

Since low prices are mainly caused by American oversupply, a decrease in American supply will have a major impact on prices. And it does look like American supply might wind down. The next graph shows how American oil production responds (eventually) to the number of oil rigs in America.

Just to clarify, “rigs” here refers to rotary rigs – the machines that drill for new oil wells. The actual extraction is done by wells, not rigs. But American oil supply shows a remarkable (lagged) covariance with rig count. From the 1990 to 2000, the number of rigs decreased, and oil supply followed it down. Then, when the number of rigs jumped in 2007, oil supply also rose with it.

Note that the number of American rigs has plummeted since the start of 2015. It is no coincidence that oil prices hit a record low in January 2015. At these paltry prices, oil companies have less of an impetus to dig for more oil.

The break-even price for shale oil varies according to the basin (reservoir) it comes from. A barrel from Bakken-Parshall-Sanish (proven reserves: 1 billion barrels) costs $60, while a barrel from Utica-Condensate (4.5 billion barrels) costs $95. The reserve-weighted average price is $76.50. These figures were calculated by Wood McKenzie, an oil consulting firm, and can be viewed in detail here.

As the number of rigs has halved to 800, the United States will not be able to keep up its record supply. Keep in mind that wells are running dry all the time, so less rigging will eventually mean less oil. Perhaps finally, the glut is about to end, with consequences for oil prices. To put things in perspective, the last time America had only 800 rigs (end January 2011), oil was at $97 a barrel.

Oil probably will not return to $100 a barrel. If it does, shale oil will become profitable again (the threshold is $76), American rigs will come online again, supply will increase and prices will come down again. So oil will have to find a new equilibrium price to be stable. A reasonable level to expect for this equilibrium is around $70, the break-even price for shale.

There will probably be a lag in the reduction of American supply: Note how oil supply does not immediately respond to the number of rigs. But things move faster when expectations are at play. On the 6th of April, traders realized Iranian rigs were not going to come online as fast as they thought. Oil prices rose 5% in one night. American supply does not have to come down for prices to drop: traders simply have to realize prices will come down.

Data from US Energy Information Agency and Baker Hughes, an oil rig services provider. Graphs plotted on R.

Abbas Keshvani

First, I have to congratulate you on your previous article being republished by Significance. It has been a pleasure to be a follower of your blog since its beginning and you have been coming up with excellent articles. I saw you particularly emphasising on American shale oil industry. I do agree with you on the economic perspective but from a wider perspective totally irrelevant to statistics, do you think in the long run, shale oil has the potential to compete with natural crude oil?

Thanks Khuddoos! Good question. Shale oil goes through a more expensive process than natural crude, which is why shale can cost between $40-80 per barrel, while crude from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait often costs less than $10 per barrel.

But when oil costs $55 a barrel, that means many shale companies can still be profitable. It’s just that they won’t make as much money as the Saudis.

Interestingly, the Saudis need oil to cost $80 per barrel because its one of their main sources of government revenue, seeing as how there is no income tax there!

Being a more bottoms up guy, a few comments:

1) You can abstract a portfolio of US oil and gas assets to different size and cost of extraction. Some big, some small, some low cost some high cost.

2) As a public markets investor you don’t get to see the full book and what they are producing from and getting output from at any given time. Its all a little bit opaque.

3) So if you take account of the firms incentives at any given time you can make some inferences:

a) hardcore distress / low price / Jan: Drill the best stuff for most cashflow, you need to raise money.

b) Ok prices: try to maintain output, maintain a growth story and let costs drift up.

c) Really high prices: Drill garbage and hedge it.

The implication for modelling output is that it never drops as much as it should when prices are falling and similarly there’s a lag when prices rise because a distressed co needs to hedge and lock it in. I think this is what makes the recent cuts interesting – people assume oilfields are like a light switch and we might find that US costs drift up somewhat with the headroom in pricing and that output recovers more slowly as producers have exhausted some of their best projects at least in the short term.

Thanks for the detailed thoughts Nemo!

On a firm-by-firm basis, agreed low prices should compel firms to drill *more* to increase cash flow. But not all of them will survive the episode: the Oil & Gas industry was responsible for 20 of 54 bankruptcies (companies with $500m or more liabilities) YTD, including Stone Energy which filed chapter 11 last week. This is one of the reasons US supply has tapered this year – crucial for the recovery in prices.

But you’re absolutely right that the supply taper is smaller and slower than a lot of people (myself included) thought it would be.

What’s interesting is that US supply, including shale supply, has been climbing up again since September. So I don’t know if Brent can continue rallying.