The Taiwanese dollar (TWD) soared as much as 8% this month. This would be a colossal move for any currency, but especially for TWD, which usually moves less than 0.5% daily. Folks have been scrambling to figure out who was responsible for this spectacular rally, from exporters to life insurance companies to the central bank.

It’s the balance of payments, stupid. I type this on a laptop made in Taiwan, contributing to the island’s current account surplus of 14% of its GDP. Such a bounty would ordinarily lead to appreciation of TWD, but much of it is recycled back out by life insurance companies (“lifers”) and the central bank buying foreign assets like US Treasuries. What’s more, exporters tend to retain a lot of their proceeds in foreign currency. Altogether, the trifecta of lifers, exporters, and the central bank have been building up an epic long-dollar position for years.

Central bank started selling dollars. The trifecta holding a floor under USD/TWD began to unravel in 2024. In the first half of the year, the central bank sold $9.1 billion of FX reserves — its biggest sale yet. I estimate that since then, they have picked up the pace of selling even further to an average $2 billion per month into March this year.

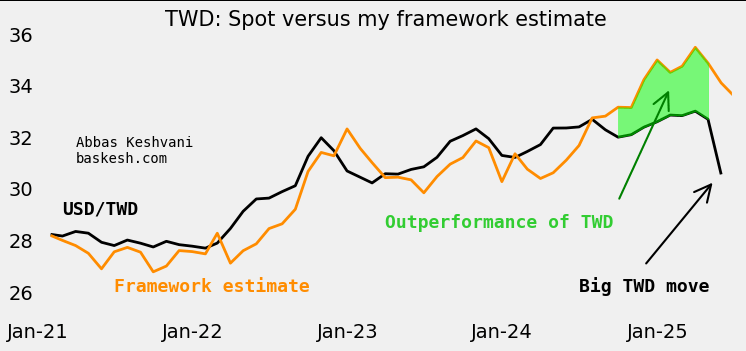

There were clues… Around the time that the central bank began selling dollars, TWD started trading stronger than my framework1 implied (this is all before the big move recently). This outperformance of TWD indicated that the currency was experiencing a regime shift. There is a lesson here: when one’s framework starts to “break down” it is a sign that something is afoot. This discrepancy from the model foreshadowed the 15 sigma move that we saw in early May 2025.

Lifers and exporters were not the first movers… To be clear, over the period that the central bank was selling dollars, insurers were actually reducing USD/TWD hedges (i.e. selling less dollars) and exporter conversion of FX proceeds had fallen to its lowest ever rate (i.e. selling less dollars). So the CBC was the first mover in the trifecta that had been keeping TWD weak until now.

… but they must have piled in. Lifers and exporters had too large a long-dollar position to not take notice of the change at the central bank. Lifers own almost $700 billion in foreign assets, and 60% of this is FX-unhedged. Exporters were holding on to their own mega-pile of dollars. Based on TWD’s historical sensitivity to flows, I estimate that the big move in early May 2025 was enabled by a conversion of around $45 billion going through. There are few parties who can manage such a colossal flow, but lifers and exporters fit the bill.

American scrutiny. So there you have it: the trifecta propping up USD/TWD started unraveling last year when the central bank began selling dollars, leading exporters and lifers to panic-sell dollars this month. But why did the central bank start this? One possible explanation is that they are keen to avoid the ire of the United States, where the Treasury department keep Taiwan on a “monitoring list” of economies whose currency practices merit scrutiny — being on the list is especially hazardous during a trade war. I would have expected the US to give Taiwan a pass, given the latter’s strategic importance, but this is not the first time that Taiwan has reduced FX intervention due to American scrutiny.

Plenty of downside for USD/TWD. Lifers could still sell another $400 billion — around ten times the amount that I estimate went through recently. If expectations for TWD cannot be anchored again, there is plenty of downside for USD/TWD. Until the central bank receives the green light from the US Treasury to buy FX, USD/TWD will be left to the preferences of lifers and exporters. This means that when the dollar is selling off, it will be prone to violent swings.

1In my framework for TWD, I model the currency against historical patterns by key actors including lifers, exporters, and the central bank.